I have a big interest in this one: I am about to be a father for the 4th time. Finding a name is tough when you’ve used up a whole bunch already, and you have to avoid clashes with friends and family with similarly-aged children.

So the Office of National Statistics baby names for 2012 – released on Monday – is a data treasure trove. What’s up, what’s down, what to avoid.

But in all the hoopla over the top names (Harry and Amelia), there is an important trend playing out. In the UK, we are getting far more diverse in how we name our kids.

There are several ways to measure this, using the ONS data that goes back to 1996.

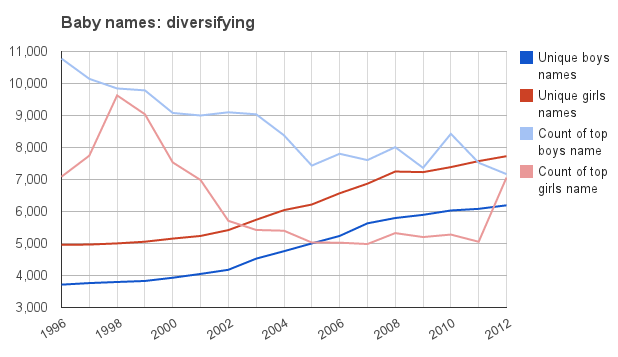

One is to look at the number of babies that are given the top name. From a peak of nearly 11,000 for boys in 1996 (the first year of available data) and 9,600 for girls in 1998, the top name has dropped to around 7,000 for boys, and until 2012, around 5,000 for girls. Ameila, the top name in 2012, has bucked the trend, with around 7,000.

But does that mean that we are simply spreading names out further among the favourites? It seems not. The ONS also lists all names that are given to three or more children in each year. The pool of names that aren’t so weird or odd as to be completely unique is rising, from under 4,000 for boys in 1996 to over 6,000 now; and under 5,000 for girls to nearly 8,000 in the same period.

(The Independent reported that there were 28,000 different boys’ names and over 36,000 different girls’ names in 2012 – which means there are a HUGE mass of names that aren’t listed by ONS which have just one or two occurences. Roughly 28,000 names have one or two occurences – out of 350,000 births, that’s a lot. But I’ve worked from the ONS dataset which gives three or more instances of each name.)

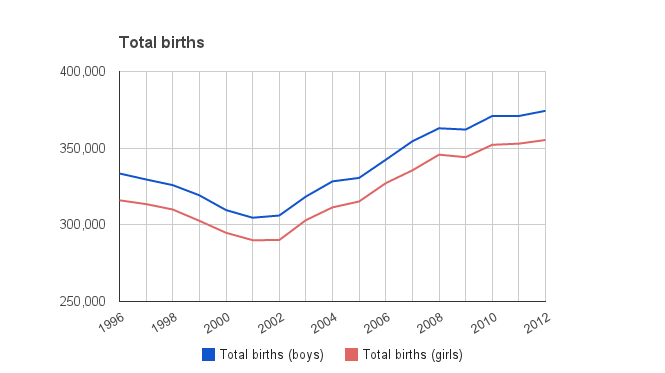

That could be partially explained by simply more overall births – and after a drop to 2002, the birth rate has indeed picked up.

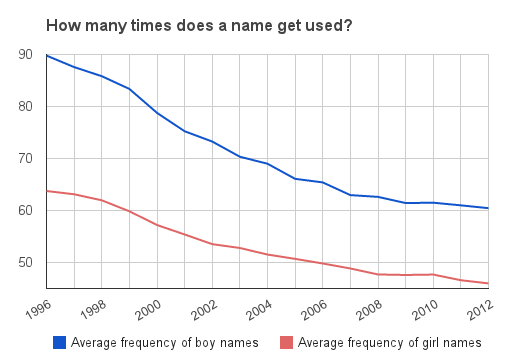

But we can easily factor that in: the average frequency of names for both boys and girls (ie the total births divided by the number of unique names used 3 or more times) is going down consistently over the period.

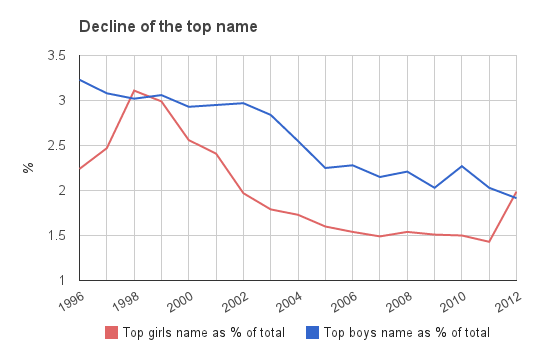

Equally, we can look at the number of times the top name is used as a percentage of the total births for boys and girls – and this is also heading down, with over 3 per cent of boys being given the top name in 1996, to under 2 per cent now. The girls top name has fluctuated more, but the trend is similar.

The divergence between the results for girls and boys shows that we have always been more creative with girls names – but the diversification trend is happening for both genders.

Why is this happening?

One answer may be immigration. As the UK gets more people from other countries, so it will get a greater diversity of names. This explains the higher number of unique names.

But that doesn’t explain the rapid decline in the number of times the top name is used. That implies we are getting more creative.

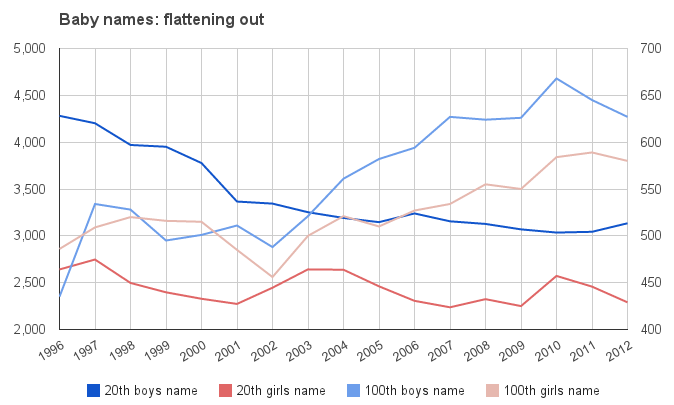

And in fact, if we look at the number of times the 20th name is given, and the 100th, there is an interesting pattern. For both girls and boys, the 20th name is also declining in popularity, but not as dramatically as for the top name. But the 100th name is generally getting more popular over time. That implies we are searching for more interesting names – the 100th most popular name is not exactly mainstream.

How far can this go? For boys, a lot further, clearly, as boys names lag behind girls in terms of diversity. Overall, there may be no end to it. You can imagine almost limitless variations on some names, as well as ever more exotic places and made-up names. Then there are hypenated versions: there were 19 Lilly-somethings alone last year. And there are parents perhaps trying to get their kids noticed by alphabetical means – there are 69 girls names in the 2012 data that start with two As, compared to 17 in 1996. And there were 125 girls names starting with Z in 2012 – compared to 74 in 1996.

Parents want their kids to stand out, it seems.

Data for all charts from ONS