The Boat Race is a bizarre event in many ways. The course is incredibly winding and gives a potentially huge advantage to the crew on the Surrey station (the south side). It’s elitist. The participants are typically now international rowers rather than amateur undergraduates. It’s way longer (over 4 miles) than usual rowing races (2k).

But there are two other odd things going on.

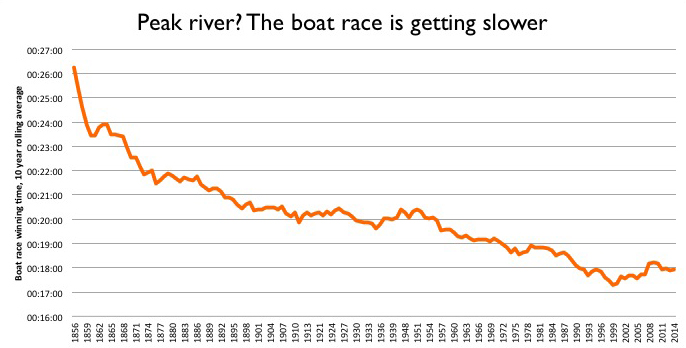

1) The race is getting slower

For many years, as boat technology improved and crews trained harder and smarter, and the rowers became international pros, the winning time came down. From the 1950s to 2000, typical times went from around 20 minutes to 17. The course record was set in 1998, at 16:19 by Cambridge. From 1996 to 2005, 5 of the 10 winning times were sub-17 seconds.

But since 2005, there have been none below the 17 second mark. As the chart below of the rolling 10-year average shows, since 1999 the times are getting slower. (I’ve used the 10-year average to smooth out what is otherwise a very bumpy chart, and show the trend. The average also mitigates the impact of the bad-weather years.)

Why the drop in pace? It’s hard to say for sure. My guess is that technological and fitness improvements are now very incremental. The shift to a global talent pool happened a while back. Instead, the races are tight, with clashing oars and cat-and-mouse tactics. It’s all about winning, not the clock.

This leads to the second odd thing:

2) The reserve crews are frequently quicker

Obviously, you would expect the Blue crew to beat the reserves (Goldie of Cambridge, Isis of Oxford). But some years the reserves, who race just before the Blues, are quicker. In fact, in seven of the last 18 years, the reserve crews have registered a faster time. The average gap between the winning times is also narrowing.

This suggests that there is a deeper pool of talent available to both teams. But it also backs up the idea that the Blue race is all about winning.

In brief: the company has changed the watermark from an obstructive, possessive gesture to a helpful, open one. It is not longer a simple stamp across the image, but a cleaner box with a short-form URL and a photographer credit.

In brief: the company has changed the watermark from an obstructive, possessive gesture to a helpful, open one. It is not longer a simple stamp across the image, but a cleaner box with a short-form URL and a photographer credit.