At the end of October, there were the yearly “news” pieces (here, here, everywhere) arguing about the merits (or lack of) for turning back the clocks in the UK.

The arguments trotted out in the press are fairly well-rehearsed now. They boil down to four main areas:

– Lighter evenings are better for the population in general and that’s when we want to do things. This clocks thing is for farmers in Scotland.

– We shouldn’t make our children walk home from school in the dark

– It’s better to be in sync with Europe

– Changing the clocks is annoying for people

Let’s make some assumptions. Most schools have kids in from 8.30am and close at 3.30pm, and most adults get to work around 9am and finish work around 5 or 6pm.

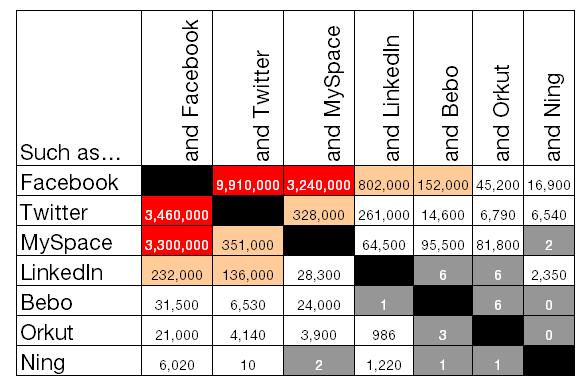

The problem here is no-one is looking at the data. Here they are in html and in google doc (data from timeanddate.com).

Quite simply, for most of the year there isn’t a problem for school children. Leaving aside whether they are picked up in cars, and whether any child old enough to walk home can do so quite perfectly well in the dark, the fact is that they don’t. The earliest sunset time in London, according to the data, is 3.51pm – 20 minutes after school usually ends. The sunrise time is around 7.55am at that time – when most children would be leaving for school. If this really is about our precious offspring, then the clocks in winter seem to fit the school day rather well. Since when should children be any safer going to school in the dark in the morning than in the evening? By moving the clocks forward an hour in mid-winter sunset would be at just after 9am in late December and early January.

Well, what about the rest of us? Don’t we want to play sport after work and enjoy a cafe-culture lifestyle in the evenings? Perhaps. But assuming that we need sunset to be 7pm or later (so we can get out of work and do something), pushing the clocks forward an hour in winter would mean we free up 16 days in March, and 26 days in November – less than 2 months in the year. It’s not exactly life-changing, is it?

And if we did that, the winter mornings would be, well, a little depressing, wouldn’t they? For 32 days in 2010, it wouldn’t be sunrise until after 9am – when most people are in work. And it would be sunset every one of those days before 5.25pm – a whole working day in the dark for some people, especially those office-bound workers behind a desk.

The other arguments are so poorly thought out it’s a joke.

Scottish farmers don’t care, apparently. (There’s the obvious solution of Scotland adopting another timezone if it was really necessary.) So let’s ignore that.

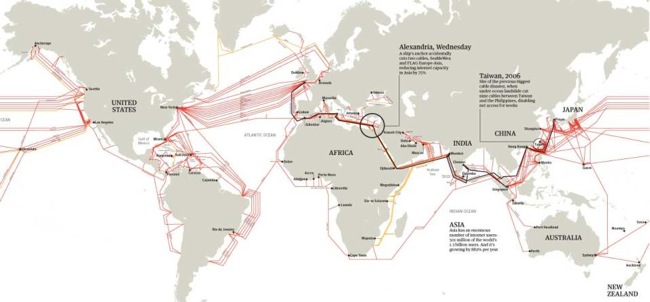

Being in sync with Europe would push the UK another hour away from US time. Which is more important – being the same as Europe when it’s only one hour out, or six hours different to New York – and nine from LA when five and eight is bad enough? Is there any proof that we lose business by being out of sync with Europe? And what would it mean for our US business? I haven’t seen any coherent answers to this, but my instinct is that it’s not a simple win-win – there are complex knock-ons we may not have foreseen. What does reducing an hour of markets trading overlap with the US do to banking?

What about health benefits? Again, the even the most balanced pieces have so many assumptions and caveats that it’s hard to point to any one major benefit, sensible as many of the suggestions seem.

Of course changing the clocks is annoying, especially if you have around 20 devices in the home that run off a timer. But more and more of them update automatically anyway – internet radios, TV hard drives, mobile phones. The connected home takes away much of that hassle. We had to change three clocks this time around – hardly a problem.

I’d personally rather the clocks didn’t shift, and we stayed consistently an hour ahead. But if we are to make an economic argument, which is what journalists and columnists are sort-of doing when they talk about benefits to people or society, then let’s use the data to back it up. Otherwise it’s just a yearly copy-and-paste job.