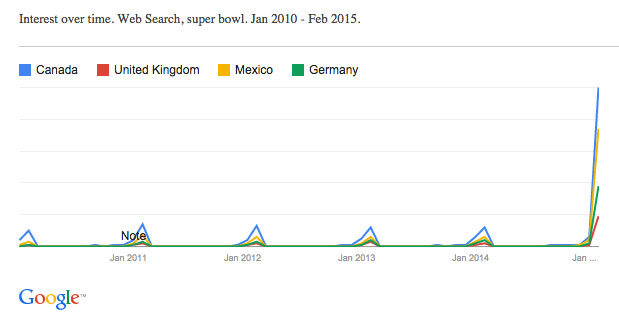

A slightly worrisome chart on the BBC this week in the run up to the opening 6 Nations match between England and Wales. It showed the average points difference for each match since 2000, with a big uptick at the end. Higher points difference means one-sided matches, surely? And that isn’t good for nail-biting matches, and crowd entertainment.

Here’s that BBC chart:

But does that tell the whole story? Perhaps not.

Points difference is only one aspect of a game. An open game which ends 40-30 is clearly more exiting than one that ended 15-5. The same ten-point difference doesn’t convey the excitement in the first game.

Clearly total points is also important. But total points alone clearly doesn’t tell the whole story either. 57-3 is hardly as exciting than 33-27.

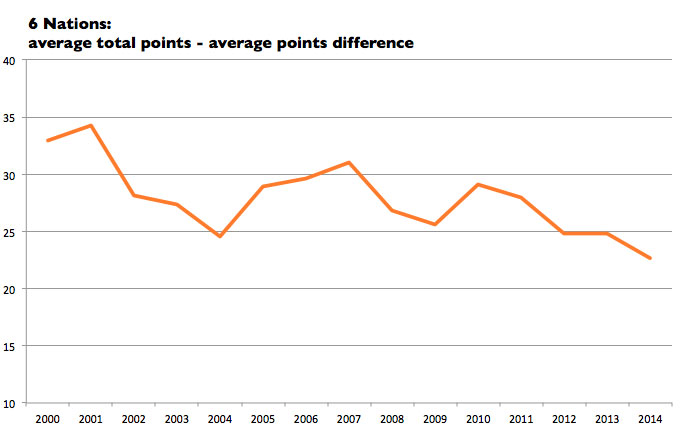

So ideally, we want high-scoring games with a small points difference. If we take the average total points per game and subtract the points difference, that gives us some idea of excitement, at least from the scoreline. It means a 23-20 game is more exciting than 6-3, as it would score 40 (23+20-3) points compared to 6 (6+3-3).

So what does the chart show? The total points scored minus the difference in points (TP-DP) is dropping over the years, and is now at just 22.7 from being over 30 in the first years of the 6 Nations. There was an initial decline, and then with breakdown rule changes, excitement increases to 2007; but then the decline starts again. We want the line on the chart to be trending up, not down.

That’s not good. But what about the Italy effect? Italy, when they were introduced to the 6 Nations, took a few big losses as the team became used to the standard of competition. They lost 80-23 to England in 2001. The 12 times that a team has lost by 40 points or more in the 6 Nations, Italy have been the loser eight times, and most of those were pre-2006.

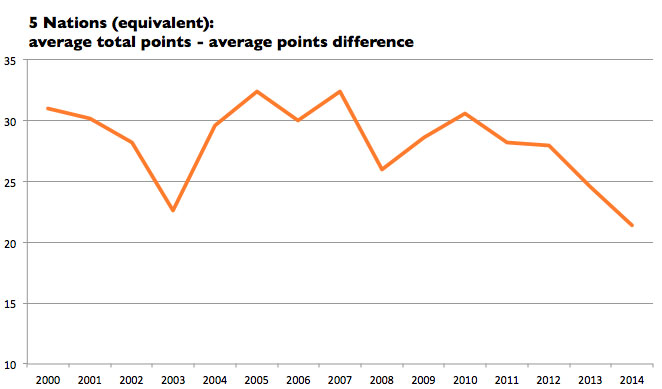

So let’s take Italy out of the equation. Of the old 5 Nations teams, has it got more or less exciting?

It’s the same pattern, only more pronounced. There is a sharp decline to 2003; an increase to 2007; and then a drop from 2010.

The worrying thing is that we are at a low: it’s 21.4, when several years had TP-DP scores of over 30.

Time for further rule changes? Who knows? Scores only tell you so much: a low-scoring match with a sudden try at the end can still be a gripping game. But then, scores on average will tell us something. If they are anything to go by, the 6 Nations is getting one-sided, and, I hate to say it, a bit dull.