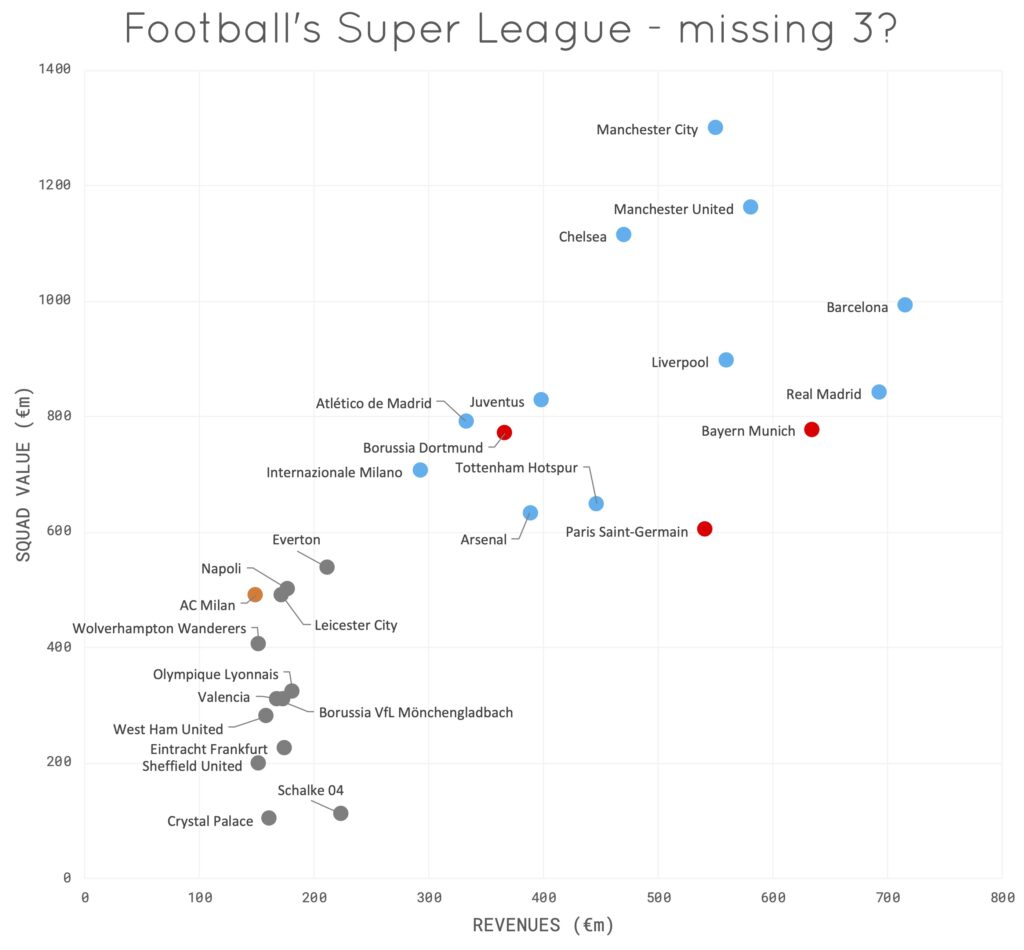

The European Super League is a bust. As the 6 English clubs pulled out, there was no way it would work.

The mistake that most commentators are making is this: the clubs that made up the 12 initial members are NOT one and the same. They don’t have the same goals, ownership structures or ethos. It was remarkable that they even got together at all.

You can think of the 12 clubs in the following five categories: US-owned; Petro-dollar; Poor Euro royalty; Faceless business; Family business

Of the 12, they fall into the following categories like this:

US-owned: Arsenal, Liverpool, Manchester United, AC Milan

Petro-dollar: Manchester City, Chelsea

Poor Euro royalty: Barcelona, Real Madrid

Family Business: Altletico Madrid, Juventus

Faceless business: Tottenham, Inter Milan

Each has their own interests, but they are most closely aligned in those groupings. In detail:

US-owned

The US-owned clubs have owners who see nothing wrong with closed leagues. Most US leagues work perfectly well in this way – but that’s because they have levelers – the draft, salary caps and so on. The US owners want to maximise revenue, guarantee glamour match-ups, and cut the dross. This is business, after all. Plus, the US sees no issue with long-distance rivaliries. Seattle – Miami is four times further than London – Milan. They totally misjudged the backlash. Whoops.

Upshot: The Super League makes sense structurally and financially to the US business mind

Petro-dollar

You can chuck PSG in the mix here as a counterpart. Why do these owners own these clubs? To launder their reputations and oil money. Manchester City want to be benevolent owners. They have invested heavily in the local area, and want to be seen to care. Roman Abramovich wants to be welcome in London – Putin’s Russia is a risky place to be. They have money – so why do they need to rock the boat? The only real motivation is for glory – if there’s a big tournament going on with your rivals, you want a piece of the action. The calculus was that the fans would go along with it. They didn’t. PSG saw the ESL for what it was: a poorly-thought out half-idea, and ran a mile.

Upshot: Never that committed

Poor Euro royalty

Barca and Real are both in a financial mess with big debts. Owned by supporters but somehow controlled by horrible chairmen, the ESL made total sense. Big payday, cut the matches with the minnows, keep the gravy train rolling.

Upshot: The Super League makes total sense financially

Family business

Hard to say what the motivation is here. Super League money would be nice, but these clubs are doing OK overall. Why rock the boat? Not being left behind is one motivation, added to a bonanza payday, but the ire of the fanbase was a big risk.

Upshot: Poor call – should have seen the backlash coming

Faceless business

Money isn’t an issue; nor is reputation. Again, the motivation to not be left out is strong; the profit motive always a nice-to-have. Ultimately, these clubs don’t have quite the same history as their bigger local rivals and need to move with the times. If that meant Super League, so be it

Upshot: can take it or leave it, just want to be part of the gang

The Euros start today. And go on for a bit, and a bit longer, and then eventually there will be a final, I promise.

The Euros start today. And go on for a bit, and a bit longer, and then eventually there will be a final, I promise.

Sport is inherently unequal. Talent and skills are not distributed fairly, and it would be a far more boring world if they were.

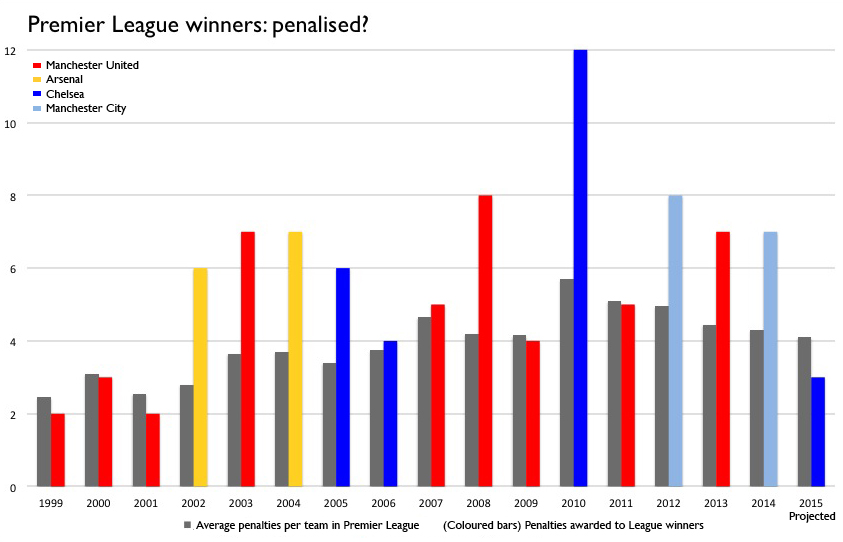

Sport is inherently unequal. Talent and skills are not distributed fairly, and it would be a far more boring world if they were. Chelsea took the unusual step of

Chelsea took the unusual step of