Isn’t Fifa simply awful? Having awarded Qatar the 2022 World Cup in less-than-savoury circumstances, now it has the brass neck to move the event to Winter to avoid the scorching heat! Shame.

A quick read of most opinion pages suggests that this is a terrible idea for a clutch of reasons: Europe’s football leagues are thrown into disarray; outdoor screenings won’t work; it will ruin Christmas; the NFL(!) will compete with US attention; it’s a summer event, dammit.

Let’s quickly dismiss a few of the frothier objections: pubs will do fine; it won’t ruin Christmas; do we seriously think the US can only watch one sport at a time? So it is supposed to be a summer event. But having given Qatar the tournament in such a dodgy way, this is hardly the biggest thing to get worked up about.

But how about those European leagues being messed about? Surely there’s something in that?

Well, there are two options. One is to suspend matches while the World Cup is on. The other is to keep playing.

For some reason, only option 1 seems to be the course of action. In which case, La Liga and the Premier League and others will have to start a few weeks early and finish a few weeks late. Hardly the end of the world, is it? The Guardian has put together how the season might look, and, to me, it doesn’t seem too bad.

But what about option 2: play on? That’s what the leagues do during the African Cup of Nations, after all. It is also what county cricket teams do when England play Tests, T20, and One-day Internationals. It’s what the rugby clubs do when the 6 Nations and Autumn internationals are on.

What would the impact be on the leagues? Well, if we take the 2014 World Cup as any guide, the breakdown of players from each league went like this:

| League |

World Cup players |

| England |

119 |

| Italy |

81 |

| Germany |

78 |

| Spain |

64 |

| France |

46 |

| Russia |

34 |

| Mexico |

26 |

| Turkey |

26 |

| Portugal |

23 |

| Netherlands |

20 |

At first glance, it’s pretty obvious that the leagues that will be most hampered in 2022 are those of England, Italy, Germany and Spain. However, In terms of the overall players, Germany’s World Cup burden is slightly higher than Italy’s, as the league has 18 teams compared to the 20 in the others. If we use the current squad sizes of all the teams in those four leagues, around 21 per cent of the Premiership’s 550-plus players would be off to the World Cup, over 15 per cent of the Bundesliga’s players, just under 15 per cent of Serie A would go, and 12 per cent of La Liga. It’s hardly an entire league – the Premiership would lose one in five players.

But of course, the burden isn’t spread equally around. In 2014 the Premiership had five clubs (Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City and Manchester United) with 10 or more players going to the World Cup. All the other teams had 6 or fewer. In other leagues there was a similar skewing: Bayern Munich had 15 World Cup representatives, Barcelona had 13 and Real Madrid had 12. Juventus and Napoli had 12 players in Brazil 2014.

What would the solution be? If the leagues insisted in playing during the World Cup, their biggest clubs would suffer disproportionately. In the era of vastly unequal resources, that might be a rather positive outcome: in the run up to 2022, the bigger clubs would have to expand their squads with home-grown and non-international players; it might mean they become reluctant to sign a World Cup-bound player. However, this isn’t for the entire season – it’s probably for six or seven matches. It would make the league more uncertain, that’s for sure. Smaller teams such as Southampton and West Ham might well vote for it. In fact, put to an equal vote, the majority of Premiership clubs should be in favour of continuing to play during the World Cup.

However, the big clubs are never going to go along with this. For example, Chelsea, with a first team squad of 24 including 12 World Cup players, would struggle to field a team without calling up a host of reserves.

The bigger issue would be gate receipts and advertising. Shorn of the bigger star names, bar the odd exception (such as Gareth Bale), the big European clubs would face a temporary tail-off of interest. It would be a “downgraded product”. And that would never do. Competing head-on with the World Cup would only have one winner: fans want to see the best players in action.

Given that the Premiership seems utterly focused on squeezing every commercial drop it can, the idea of playing on is a non-starter. Which is a shame, as football in England and Spain could do with a rebalancing of power, however temporary.

The only other scenario in which the European leagues would play on is if they force their players to boycott the World Cup. The ramifications of that would be huge. In fact, it would be the most divisive moment in football history, and possibly spell the end of international football in its current form.

Somehow, I don’t think Fifa will let that happen.

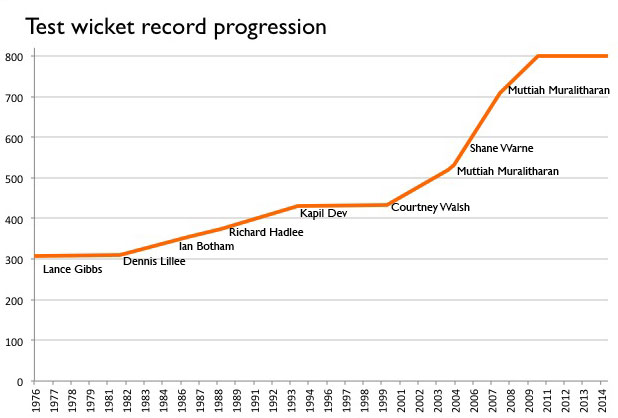

Amid all the articles congratulating James Anderson for surpassing Ian Botham as England’s all-time Test wicket taker, I’ve not seen one to put the numbers in perspective. It’s a fine achievement, certainly, but compared to other countries, it’s pretty small beer.

Amid all the articles congratulating James Anderson for surpassing Ian Botham as England’s all-time Test wicket taker, I’ve not seen one to put the numbers in perspective. It’s a fine achievement, certainly, but compared to other countries, it’s pretty small beer.

I’m still reeling from the 6 Nations final weekend. I was lucky enough to be at Twickenham, and rugby matches like that are remarkable. But the stats from the weekend are remarkable too.

I’m still reeling from the 6 Nations final weekend. I was lucky enough to be at Twickenham, and rugby matches like that are remarkable. But the stats from the weekend are remarkable too.

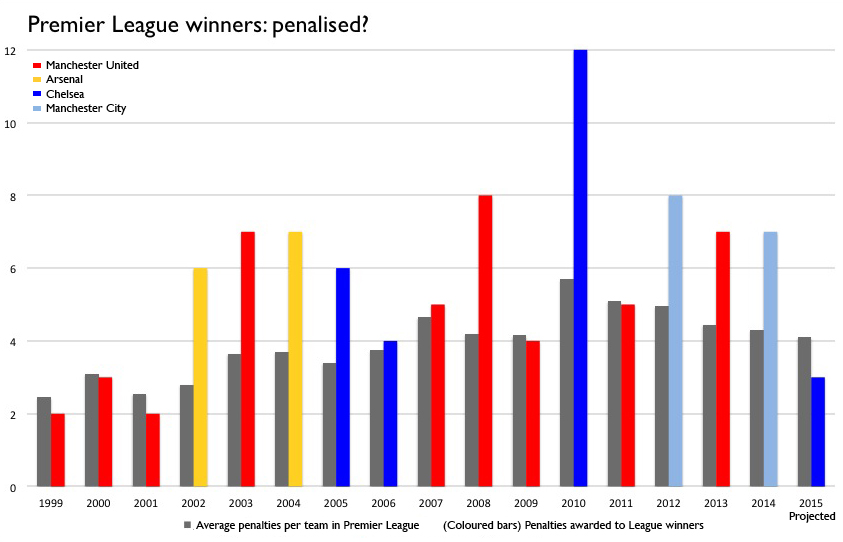

Chelsea took the unusual step of

Chelsea took the unusual step of

Who would be a bowler these days? Specifically, who would be a West Indian bowler playing South Africa?

Who would be a bowler these days? Specifically, who would be a West Indian bowler playing South Africa?